This is part of a series called, Ask a Psychologist at Education Week

July 08, 2020 – Jamie Carroll and David Yeager

Question: During distance learning, I think I’ve been teaching my students to use a growth mindset. But how do I know when it’s working—and when it’s not?

In the classroom, teachers can usually tell when a student is feeling discouraged. Maybe they put their head down. Maybe they throw their hands up in defeat. Or start copying answers. If you’ve been establishing a growth-mindset culture, you can emphasize everyone’s potential to learn, even when the work is hard.

But it’s harder to see the early-warning signs of disengagement—and sustain a culture of learning—in remote or blended learning contexts.

We asked Dana Stiles, an OnRamps statistics teacher at Bowie High School in Austin, Texas, about how she handled this challenge during COVID-19.

First, the good news: Dana thinks that distance learning might have improved some students’ growth-mindset behaviors, such as help-seeking, because it removes a lot of the social comparisons that teens are especially apt to make. In a regular classroom, some students are afraid to ask for help because they don’t want to look dumb in front of their peers or they think they are bothering you.

But distance made it harder for her to know who needed more support. “In the classroom, I was able to take their temperature [metaphorically] by standing at the door as they walked in—knowing where their head is at and any personal battles they’re facing and challenges they’re dealing with,” she explained. But during COVID-19, she had to reach out to students proactively to see how they were doing.

She started by sending personal, physical letters in the mail to students she knew had challenging home lives or other factors that might get in the way of learning. She used Calendly to give students the opportunity to sign up for one-on-one video meetings. Using the Remind app, she sent personal messages to students who were not engaging in material with specific questions they had to respond to.

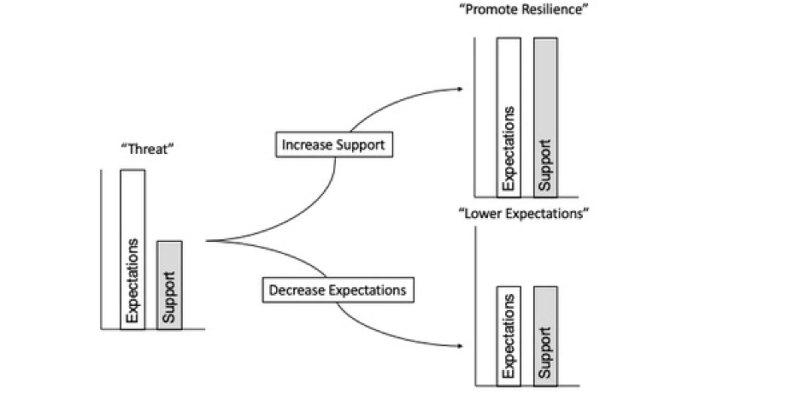

In the video meetings, she could keep the discussion personal and brief, covering just two questions: How are you doing and feeling? And how can I support you as you meet the ambitious learning goals in this class? These two questions let students know that you care about them as people and that your priority is their learning—not evaluating or judging them.

Students can then feel free to challenge themselves and reach out for help when they’re stuck.

Contacting students individually is time-consuming and challenging, but Dana says it’s well worth the effort you put in: “The kids actually thank you for it because you’re personalizing what they need to do based on their results and their reflections.”